Victors of the panathenaic games

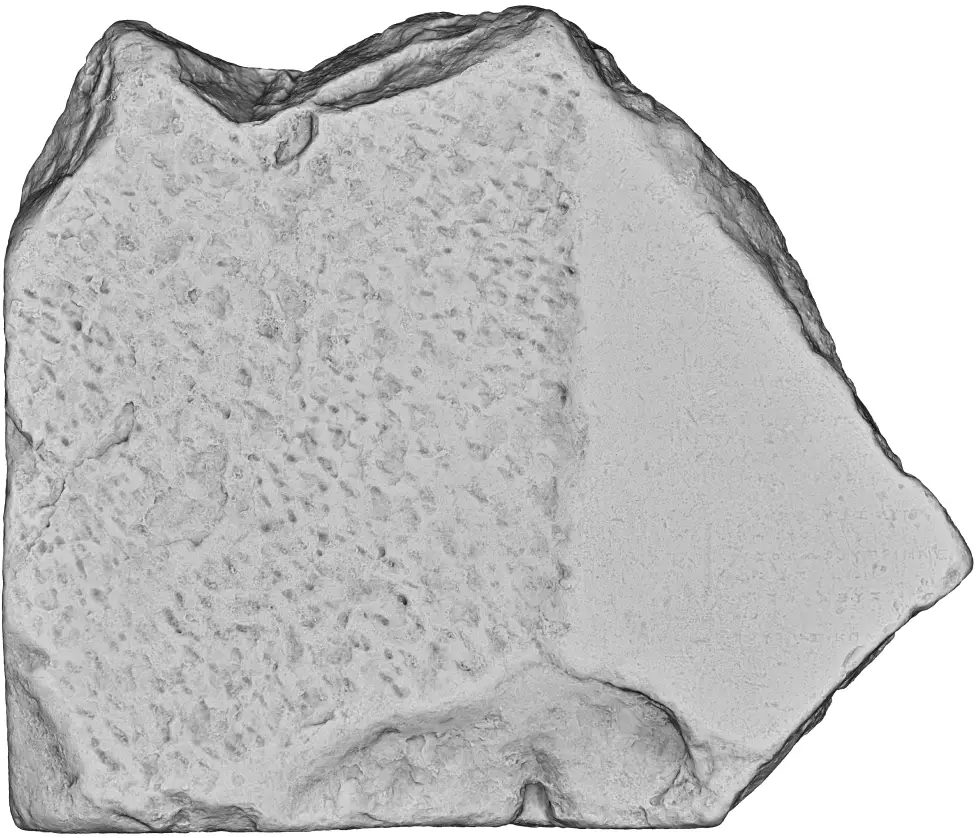

This heavy marble slab was discovered by the Agora excavations after the dismantling of a 19th century wall. The left and and bottom sides of the slab are intact, but the inscription has been through some tough times! Its original surface was cut down when the stone was reused, and the inscribed surface to the right is badly scraped.

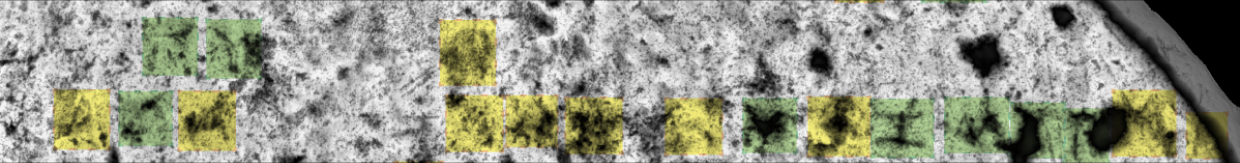

View of the surface under ambient occlusion shading. The left two-thirds of the stone was hacked away, but the original surface and text is partly preserved to the right.

Through some impressive detective work, Stephen V. Tracy was able to link this stone to several others that share a distinctive pattern: they all list athletic contests from the Panathenaic games, followed by the name of the victor. The other stones are better preserved. Two large sections are in Athens, others were published in the 19th century but were since lost. One slab had even been taken to Italy, where it was recently rediscovered in a small museum in Pesaro. These inscriptions all seem to have been set up together in a monument somewhere in the Agora that recorded the victors of the athletic and equestrian contests held every four years between 222 and 150 BCE, with a column added after every games.

WHAT'S AT STAKE

The stone, Agora I 6701, is really difficult to read! Already, three publications between 2015 and 2024, going back and forth between Tracy and another prominent expert in ancient Athens, Julia Shear, agree on most points but have presented alternate reconstructions of the games, victors’ names, and the relative sequence of the events. For example, the 2024 study proposes that this stone was carved for the games of 218 rather than 190 BCE, which had been suggested in the 2015 article.

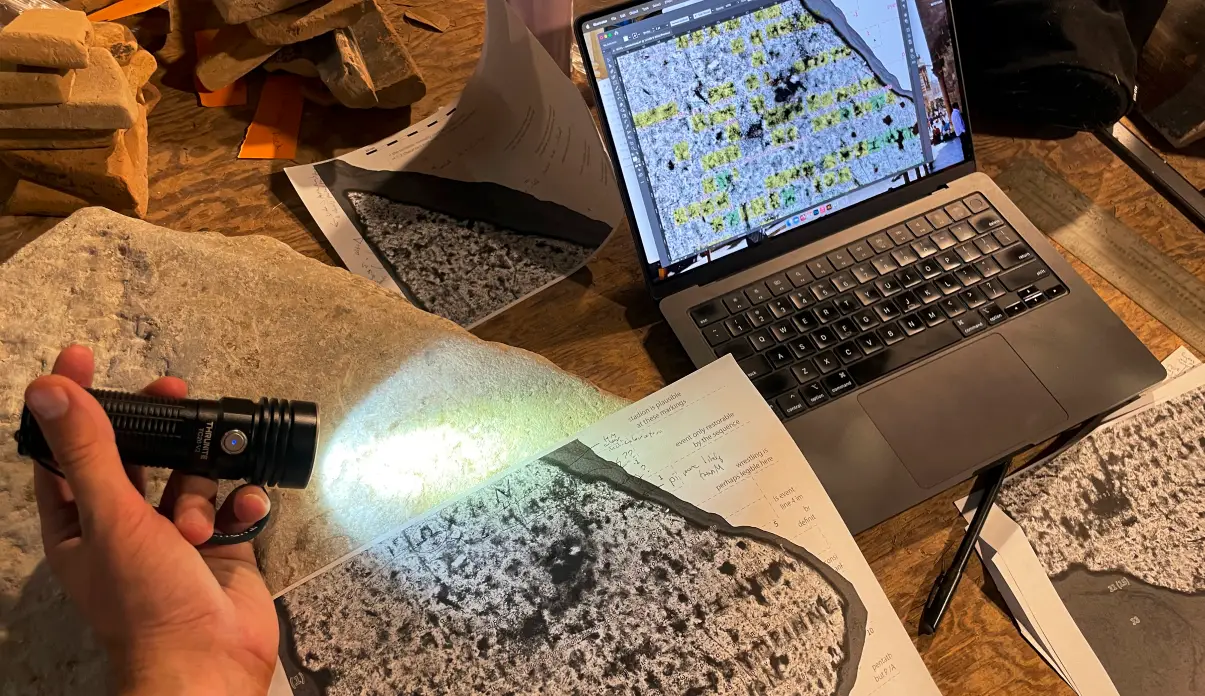

This is an ideal situation to try out the new RDI techniques developed by DEVA.

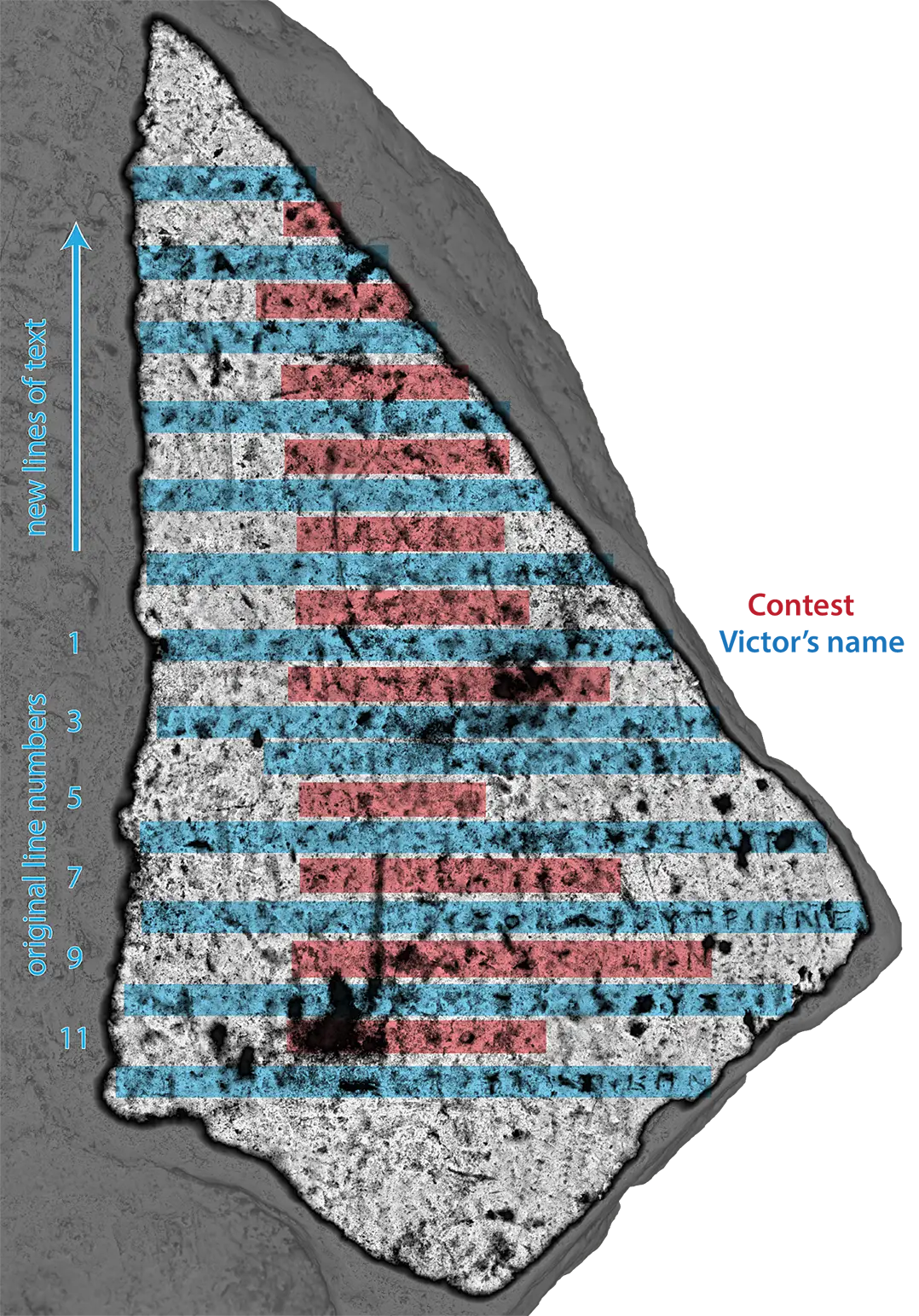

One reason is that the victory lists have a consistent order. The better-preserved lists refer to dozens of contents that would have been scheduled over a few days. There are were footraces of various lengths and types (δόλιχον, στάδιον, δίαυλον, etc.), as well as combat by boxing (πυγμήν), wrestling (πάλην), and a brutal combination called the pankration (παγκράτιον). Adolescents, young men, and adults competed for separate prizes. Although the many equestrian events could change from one year to another, the athletic events had been established for centuries and were repeated in the same order.

As long as we can read a few of the sports named on stone I 6701, we can predict some of the missing ones due to this established sequence.

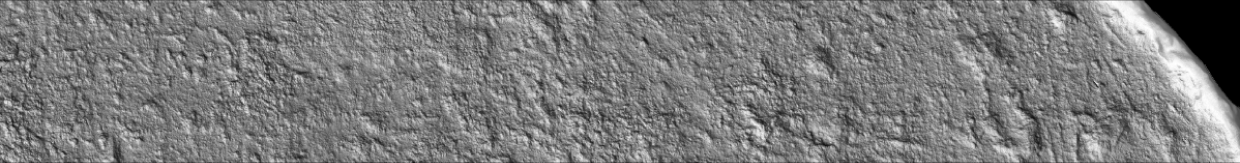

In fact, the depth-mapping layer in the RDI shows us faint, but unmistakable indentations where the original surface of the stone is preserved. The surface is too badly scratched to read many letters, but we can see the shadows of lettering. This allows us to add a dozen lines before the official transcription begins at line 1. We might not be able to read full names here, but the RDI does suggest that a lot more of the stone is left than we had previously assumed.

VIEW THE RDI LAYERS

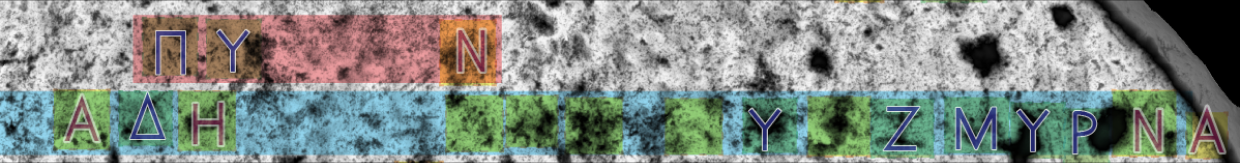

Another example is here, at lines 5 and 6, naming the winner of the boxing contest, the πυγμήν:

This contest was restored by position, since it should precede the pankration, which is clear enough in the next line. But none of the characters had been recognized in the past studies by Tracy and Shear, who each independently examined the stone and a paper squeeze in order to discern as much of the original lettering as possible.

RESULTS & FUTURE PROSPECTS

We were very excited when we found the first two letters and probably the last letter of the boxing contest on the actual stone. With the guidance of the enhanced RDI layers, it was possible to discern these strokes under raking light. If we didn’t know where to look, however, the strokes are lost within a confusing field of scratches – the proverbial needle in a haystack.

The experts had been able to read the end of the next line naming the victor. His name is mostly effaced, but his hometown is recognizable: Ζμυρ[ναῖος], or Smyrna – called Izmir in modern Türkiye. The RDI imagery confirms their reading, and it reveals traces of several additional letters. The ‘N’ of Smyrna was assumed to be lost, but it is actually pretty clear in the digital images. We can even see the start of the next letter, ‘A’. To the left, a few characters from the name, though not enough to restore it with any confidence.

The next steps will be more research. We should examine the published transcriptions of I 6701 against the new RDI layers more methodically, and consider the possible sequences of athletic contests that be restored over the faint traces in the upper lines. A future publication of the stone will also examine how it may have fit together with the other blocks from this fascinating Athenian monument.

REFERENCES

Tracy, S.V., and C. Habicht. 1991. “New and Old Panathenaic Victor Lists,” Hesperia 60, pp. 187–236.

Tracy, S.V. 2015. “Agora I 6701: A Panathenaic Victor List of ca. 190 B.C.,” Hesperia 84, pp. 713–721.

Shear, J.L. 2021. Serving Athena: The Festival of the Panathenaia and the Construction of Athenian Identities, Cambridge University Press, pp. 380–89.

Tracy, S.V. 2023. “A New edition of the List of Panathenaic Victors IG II2 2313,” Hesperia 92, pp. 515–535.

Tracy, S.V. 2024. “Panathenaic Victor Lists of the Years 229–162 B.C. Agora I 6701 Revisited.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 229, pp. 81–84.

More about inscription I 6701 on the Agora Digital Collections